The COVID-19 pandemic has placed at risk the substantial investment of state and local governments in the tourism and hospitality industries. Publicly funded destination marketing organizations (“DMOs”), tourism agencies, and convention centers face budget shortfalls, staffing reductions, and growing financial uncertainty. Targeted federal aid is urgently needed to support DMOs, tourism agencies, and convention centers whose work is critical to the recovery of vital sectors of the US economy.

Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis has shined a spotlight on the importance of public sector investment in the hospitality and tourism industries. State and local governments support the industry through spending on tourism promotion, destination management, and tourism infrastructure such as convention centers, stadiums, and arenas. With drastically reduced resources, continued public sector investment in the industry is in jeopardy.Federal aid to the hospitality and tourism industry, thus far, has provided some direct aid to private sector partners and owners of properties affected by the pandemic, primarily through Small Business Administration (“SBA”) loans and grants, but these amounts have not been sufficient to cover the extreme industry-wide financial losses. The U.S. Travel Association, in tandem with Tourism Economics, projects cumulative losses since the beginning of March totaling $195 billion for the travel industry.[1] Estimates of the quantifiable effect of COVID-19 on the industry vary; however, the common thread of these projections show an industry at risk.

The federal government provided roughly $274 billion in aid to state and local governments in the CARES Act.[2] But most of that aid was directed at paying for COVID-19 pandemic response and cannot be used for revenue replacement. Federal aid that would address revenue shortfalls is currently being debated in the US Congress. Such aid could indirectly support the hospitality and tourism industries by shoring up the overall fiscal health of state and local governments and preventing the diversion of hospitality and tourism spending to other services.

Targeted aid to state and local governments, aimed at direct stimulus to the hospitality industry, may allow for faster recovery for the entire economy. The hospitality and tourism industries have proven to be the most vulnerable of industries to the COVID-19 pandemic with percentages of revenue losses far exceeding that of the overall economy. The Bureau of Economic Analysis showed a 5% decline in real GDP during the first quarter of 2020.[3] The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta projects, in the second quarter of 2020, a 52.8% decline in real GDP.[4] The Congressional Budget Office projects annual GDP growth for real GDP to only fall by 5.6% in 2020.[5] By comparison, projections of travel industry losses are greater than overall decreases in GDP. An Oxford Economics study from April 2020 projected an 81% loss in travel industry revenue in April and May 2020—with losses continuing through the rest of the year—and a decline of 45% of the travel industry’s contribution to US GDP for the year 2020.[6]

Tourism agencies and destination management organizations (“DMOs”) face dual challenges of convincing the public that travel to their destinations is safe and affordable. Additional effort will be required to secure convention, group and meeting business, rescheduling postponed events, and making health related accommodations to event organizers. This additional workload cannot be accomplished with reduced staff levels. Many convention centers rely on lodging tax revenue and other tourism taxes that support their operations and capital investments. Their continued operation and necessary capital improvements are also threatened by the dramatic reduction in revenue. Consequently, targeted relief to the tourism agencies and DMOs is an essential piece of effort to revive the hospitality and tourism industries.

The public sector engages in large public investment into the hospitality industry

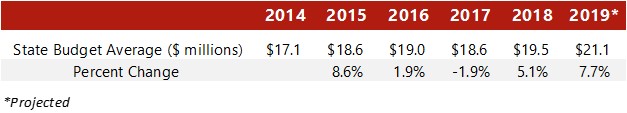

Some public sector efforts in the hospitality industry are highly visible—such as the Pure Michigan campaign and Las Vegas marketing efforts. In reality, the tourism industry as a whole relies, in part, on all contributions made by public sector partners. Taking place at the state and local level, tourism promotion, the operation of convention and visitor bureaus, and many other efforts are undertaken to ensure the health of the industry. The following figure summarizes the U.S. Travel Association’s State Tourism Office Budget Dashboard.[7]

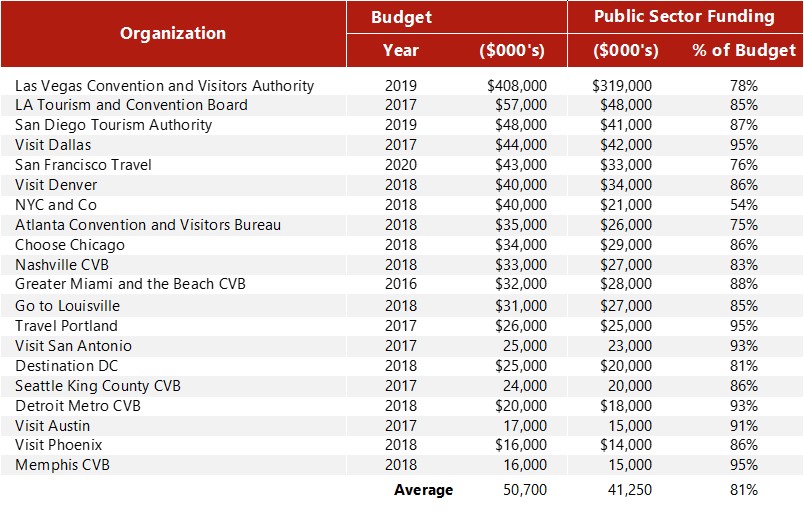

Efforts to promote tourism come from the local level as well. The following figure summarizes the budgets of the 20 largest DMOs in the US, and their reliance on public sector funding.

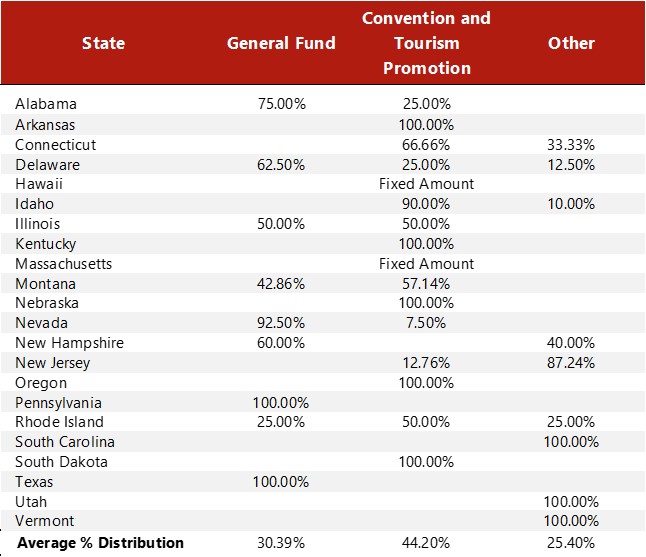

The following figure provides the distribution of lodging tax revenues for those states with a separate lodging tax.

On average, 44.2% of lodging taxes in these states go to convention and tourism promotion and 30.39% of revenues go to state general funds.

HVS previously projected that lodging tax losses in 2020 across the top 25 hotel markets in the United States could range from 52% to 60%.[9] If those same losses are applied to the 2019 revenues from states with a dedicated lodging tax, state lodging tax revenues in those states could decline from $3.47 billion in 2019 to between $1.39 and $1.65 billion in 2020. Assuming 2019 total lodging taxes in the US were $21.52 billion, the COVID-19 pandemic could reduce lodging taxes in 2020 to between $8.64 to $10.25 billion.[10]

Budgetary constraints created by COVID-19 will result in budget cuts for public sector agencies in the hospitality industry

State and local government allocation of spending on convention and tourism promotion will be affected by general revenue declines. Estimates of the magnitude of state budget shortfalls created by COVID-19 for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021 vary from 15% to 25%.- The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates state budget shortfalls reaching 15% in Fiscal Year 2020 and 25% in Fiscal Year 2021.[11]

- Moody’s Investor Services estimated that state tax revenues in Fiscal Year 2021 would fall 14.2% lower than Fiscal Year 2019 levels.[12]

- The National Conference of State Legislators has projected state revenue losses of 15 to 20%.[13]

In a status quo without federal aid, public sector agencies will suffer under a prolonged recovery

As seen in the figures and discussion above, state and local tourism agencies and DMOs rely on public funding for their operations. Given the unreliability of these public funds, state and local agencies face budget shortfalls and staffing changes that impede their ability to complete their jobs. Due to the size of its impact, the effect of COVID-19 on agency budgets may return them to levels lower than they fell in the Great Recession.Staffing changes also pose an additional issue when looking at the recovery of these agencies. For example, the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, the largest CVB in the United States by budget, saw furloughs and layoffs of 350 of its 455 employees—over 3/4ths of their staff.[15] Losses of this size, albeit some temporary, will prevent these agencies from effectively carrying out their missions. The tourism and hospitality industry has always relied on the expertise and excellence of the employees at these agencies. With these employees on the sidelines—or let go completely—the industry will face a prolonged recovery due to loss of institutional knowledge and effective manpower.

According to the U.S. Travel Association, the trade surplus from international spending in the United States peaked at $99 billion in 2015 and declined to $59 billion in 2019.[16] The Department of Commerce identified almost a 30% decline in the trade surplus as a result of the Great Recession in 2009.[17] The economic fallout from COVID-19, along with an already declining trade surplus, may push the United States to become a net exporter of tourism dollars rather than a net importer. The work of state and local agencies is pivotal to help buoy the trade surplus and continue to promote travel and tourism to and around the United States.

Remedies

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced something into each of our lives: uncertainty. Great uncertainty surrounds the longevity of the virus, the potential for a vaccine, and what the world will look like on the other side of this pandemic. But one thing is clear: state and local agencies dedicated to the tourism and hospitality industry face dramatic losses of resources that, if left unaddressed, will hinder their vital work for the foreseeable future. The federal government, knowing the impact these agencies have on tourism promotion and the economic impact of tourism, should consider targeted relief to state and local governments designed to assist these agencies.The recovery of the tourism and hospitality industry is inextricably tied to the recovery of related industries. For example, the airline industry benefits from the reintroduction of leisure and group travel. The hotel industry, which supports 8.3 million jobs, benefits from tourism and travel across the United States.[18] The list goes on and the message is the same: tourism and travel are key to the recovery of several industries and the economy writ large. State and local partners in the tourism and hospitality industry are as necessary as ever to promote safe tourism and help revitalize our struggling economy.

[1] “COVID-19 Travel Industry Research,” U.S. Travel Association, June 2, 2020 (ustravel.org).

[2] Jared Walczak, “Designing a State and Local Government Relief Package,” Tax Foundation, May 12, 2020 (taxfoundation.org).

[3] “Gross Domestic Product, 1st Quarter 2020 (Second Estimate); Corporate Profits, 1st Quarter 2020 (Preliminary Estimate),” Bureau of Economic Analysis, May 28, 2020 (bea.gov).

[4] “GDPNow,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, June 1, 2020 (frbatlanta.org).

[5] Phill Swagel, “CBO’s Current Projections of Output, Employment, and Interest Rates and a Preliminary Look at Federal Deficits for 2020 and 2021,” Congressional Budget Office, April 24, 2020 (cbo.gov).

[6] “The Impact of COVID-19 on the United States Travel Economy,” Oxford Economics, April 15, 2020 (ustravel.org).

[7] “State Tourism Office Budgets Dashboard (FY 2018-19),” U.S. Travel Association, January 29, 2019 (ustravel.org).

[8] “Welcome,” California Office of Tourism, June 2, 2020 (tourism.ca.gov).

[9] Thomas Hazinski, “HVS COVID-19 Impact on Lodging Tax Revenues,” HVS, April 20, 2020 (hvs.com).

[10] Estimate of taxable room revenues comes from taking a percentage of total rooms revenue, which we assume is equal to the total number of hotel rooms (statista.com) multiplied by the annual RevPAR reported by STR for 2019 (str.com). We multiply taxable room revenues by the average tax rate across the United States (14% as reported in the 2019 HVS Lodging Tax Study).

[11] “States Grappling with Hit to Tax Collections,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 2, 2020 (cbpp.org).

[12] “Revenue Recovery from Coronavirus Hit Will Lag GDP Revival, Prolonging Budget Woes,” Moody’s Investors Service, Apr. 24, 2020 (law360.com).

[13] “Re: Flexible Stimulus Funds for States to Stabilize Economy,” National Conference of State Legislatures, Apr. 16, 2020 (ncsl.org).

[14] Erica MacKellar, “State Tourism Office Budgets,” National Conference of State Legislatures, July 30, 2019 (ncsl.org).

[15] Hector Mejia, “LVCVA to lay off, furlough 350 employees as part of $79M budget cut,” CBS 8 News Now Las Vegas, April 14, 2020 (8newsnow.com).

[16] “Reducing the Trade Deficit by Growing International Travel,” U.S. Travel Association, February 2020 (ustravel.org).

[17] “United States Travel and Tourism Exports, Imports, and the Balance of Trade: 2012,” U.S. Department of Commerce International Trade Administration, Office of Travel and Tourism Industries (travel.trade.gov).

[18] Chuck Dobrosielski, “AH&LA projects COVID-19’s state-by-state jobs impact,” Hotel Management, March 24, 2020 (hotelmanagement.net).

0 Comments

Success

It will be displayed once approved by an administrator.

Thank you.

Error